THE CENTURY

Vol. 99 APRIL, 1920 No. 6

Roosevelt and Our Coin Designs

Letters between Theodore Roosevelt and Augustus Saint-Gaudens

Collected by Homer Saint-Gaudens

Photographs by De W. C. Ward

The versatility of Theodore Roosevelt is once more manifested in the following correspondence between the late ex-President and Augustus Saint-Gaudens, the famous sculptor and the designer of a series of American coins. Americans will be interested to learn that their President was personally conducting the campaign for a more artistic series of coinage designs.

In the winter of 1905 Theodore Roosevelt met Augustus Saint-Gaudens at a dinner in Washington, during which the conversation drifted to the subject of the old high-relief Greek coins. Saint-Gaudens had come to Washington primarily to serve, under the auspices of the park commission, with the architects Charles F. McKim and D. H. Burnham and the landscape-architect Frederick Law Olmsted on a committee gathered by the President to give criticism and advice toward maintaining the beauty of the National Capitol according to the plans of the original architect, L’Enfant. In the course of their service, whenever President and sculptor met, the latter’s opinion was sought by Mr. Roosevelt concerning the obvious subject on which Saint-Gaudens could give counsel of a high order—sculpture.

One of the most direct ways in which art may bear upon public welfare is through the coinage. Saint-Gaudens spoke with deep admiration of the Greek coins. To him they were almost the only coins worthy of consideration. Why could not the United States have coins like the Greeks, the President wished to know. If Saint-Gaudens would model them, he, the President, would cause them to be minted, since, as he expressed it, with his customary vehemence, “This is my pet crime.”

The notion of producing worthy coins might never have been carried out; the discussion and desire for them could have lapsed with the end of that dinner had either the President or the artist been a less sincere character. Each proved willing, however, in a peculiar way, to contribute something to the nation, the sculptor his genius, the statesman the energy of his position. It is an extraordinary thing that, in the midst of all his other duties and perplexities, a President had the enthusiasm to find time to discuss with Americans so unusual a topic as coinage. It is equally to the sculptor’s credit that as an artist he was willing to accept suggestions from the President.

If the letters which follow do not disclose anything else, they are remarkable for exhibiting this agreement of two great, yet dissimilar, minds upon a task that meant a service to the public—a service unique in that its aim was to produce a beautiful result and at the same time a result typically national.

Mr. Roosevelt speaks in his autobiography of his efforts toward this reform during his administration:

In addition certain things were done of which the economic bearing was more remote, but which bore directly upon our welfare, because they add to the beauty of living, and therefore to the joy of life. Securing a great artist, Saint-Gaudens, to give us the most beautiful coinage since the decay of Hellenistic Greece was one such act. In this case I had power myself to direct the mint to employ Saint-Gaudens. The first and most beautiful of his coins were issued in thousands before Congress assembled or could intervene; and a great and permanent improvement was made in the beauty of the coinage.

For two years President and sculptor gave time and energy to this task. In a certain measure their work was robbed of results by red-tape and bureaucratic idiosyncrasies. Yet the impetus of their attempt continued through succeeding administrations. As a result, while our coins cannot compare with such masterpieces as the French gold twenty-five-franc [twenty-franc?] piece by Chapl[a]in, or the silver one- and two-franc pieces by Roty, nevertheless we are free from the slough of ready-made numismatics which long tarnished the output of our mint.

From the date of the striking of the twenty-dollar and ten-dollar gold pieces designed by Saint-Gaudens, at Mr. Roosevelt’s suggestion, the change has been obvious. Beginning with the “Buffalo” nickel by James Fraser and coming down to the ten-cent piece by Adolph Weinman, the coins form a representation of sincere medal-work in this land.

From the first letter found in the Roosevelt-Saint-Gaudens correspondence, one written in 1903, Mr. Roosevelt establishes his understanding of art as an influence in our national life and voices his appreciation of the sculptor’s work. Compare his statement that, “I have no claim to be listened to about these matters, save such claim as a man of ordinary cultivation has,” with his remarks about allegory. Surely “ordinary cultivation” cannot be expected to observe and express itself so acutely in matters of art. Mr. Roosevelt wrote:

White House

WashingtonOyster Bay, N. Y.

August 3, 1903.Personal

My dear Mr. Saint-Gaudens:

Your letter was a great relief and pleasure to me. I had been told that it was you personally who had opposed ——–. I have no claim to be listened to about these matters, save such claim as a man of ordinary cultivation has. But I do think that ———, like Proctor, has done excellent work in his wild-beast figures.

By the way, I was very glad that the Grant decision in Washington went the way it did. The rejected figure, it seemed to me, fell between two schools. It suggested allegory; and yet it did not show that high quality of imagination which must be had when allegory is suggested. The figure that was taken is the figure of the great general, the great leader of men. It is not the greatest type of statue for the very reason that there is nothing of the allegorical, nothing of the highest type of the imaginative in it. But it is a good statue. Now to my mind your Sherman is the greatest statue of a commander in existence. But I can say with all sincerity that I know of no man—of course of no one living—who could have done it. To take grim, homely, old Sherman, the type and ideal of a democratic general, and put with him an allegorical figure such as you did, could result in but one of two ways— a ludicrous failure or striking the very highest note of the sculptor’s art. Thrice over for the good fortune of our countrymen, it was given to you to strike this highest note.

Always faithfully yours,

Theodore Roosevelt.

Mr. Augustus Saint-Gaudens,

Aspet, Windsor, Vermont.

To this the sculptor replied:

Aspet, Windsor, Vermont,

August 15, 1903.

… I don’t know how to thank you for your more than kind words about the “Sherman” and my other work. When I realize that you have taken the time to say this to me amid the multitude of other things on your mind, it is a fact that touches me deeply and your letter will be set aside and treasured for those who come after me. . . .

Two years later the appreciative understanding between President and sculptor grew even warmer, when the question arose regarding the inaugural medal to be struck in commemoration of Mr. Roosevelt’s taking office for the second time. Saint-Gaudens was asked to design the relief himself. He could not do so, but, with the cordial assistance of a fellow-sculptor, Mr. Adolph Weinman, for once, at least, he succeeded in producing a decent inaugural medal. In response to Mr. Roosevelt’s urgent request for Saint-Gaudens’s services, the sculptor wrote:

THE PLAYERS, 16 Gramercy Park,

Jan. 20, 1905.

Dear Mr. President:

If the inauguration medal is to be ready for March the first there is not a moment to lose. I cannot do it, but I have arranged with the man best fit to execute it in this country, Mr. Adolph Weinman. He is a most artistic nature, extremely diffident. He would do an admirable thing. He is also supple and takes suggestion intelligently. He has made one of the great Indian groups at St. Louis that would have interested you if brought to your attention. He is so interested that he begged me to fix a price.

And again:

Dear Mr. President:

General Wilson showed me the McKinley Inauguration Medal, which is so deadly that I had Weinman go down to Philadelphia. The man there who has charge of the bulk of the ordinary medals already contracted for cannot possibly do an artistic work. He is a commercial medalist with neither the means nor the power to rise above such an average. Mr. Weinman writes to General Wilson tonight that our reliefs must be put into other hands and this is to beg you to insist that the work be entrusted to Messrs. Tiffany or Gorham. Otherwise I would not answer for its not being botched.

I made studies on the train on my way up from Washington and I have struck a composition which I hope will come out well. Mr. Weinman is enthusiastic about it, and I am certain should execute it admirably. You know that the disposition of the design on the medal is nine tenths of the battle.

In other matters my composition calls for the simplest form of inscription, and here also I wish your support, of course, provided you think well of the idea. On the side of your portrait I propose placing nothing more than the words:

“Theodore Roosevelt. President of the United States.”

and on the reverse, under the emblematic design, the words:

“Washington, D.C., March 4, 1905.”

The simplicity of inscription greatly aids the dignity of the arrangement, but if you believe that more is needed, I will add it with pleasure. . . .

Soon after this, at the request of the President, Saint-Gaudens agreed to consider modeling a statue of President McKinley for a committee headed by Mr. Franklin Murphy of Newark, New Jersey. Regarding the sculptor’s desire to be of service, Mr. Roosevelt wrote:

White House

WashingtonJune 13, 1905.

My dear Mr. Saint-Gaudens:

Personally, and because of my official connection with President McKinley and individual regard for him, and moreover because of my position as in a sense the representative of the American people, I thank you from my heart for your decision.

Faithfully yours,

Theodore Roosevelt.

Mr. Augustus Saint-Gaudens,

Windsor, Vermont.

On looking into the matter, however, Saint-Gaudens found that the funds the committee felt they could spend were inadequate, so he gave up the commission.

Then followed this letter of thanks from Mr. Roosevelt for Saint-Gaudens’s efforts on the inaugural medal:

White House

WashingtonOyster Bay, N.Y.

July 8, 1905.My dear Mr. Saint-Gaudens:

Really I do not know whether to thank most Frank Millet, who first put it in my rather dense head that we ought to have a great artist to design these medals, or most to thank you for consenting to undertake the work. My dear fellow, I am very grateful to you, and I am very proud to have been able to associate you in some way with my administration. I like the medals immensely; but that goes without saying; for the work is eminently characteristic of you. Thank Heaven, we have at last some artistic work of permanent worth done for the government!

Will you present my compliments and thanks to Mr. Weinman? Perhaps you know that we got him to undertake the life-saving medals also.

I was rather exasperated with the McKinley Memorial Committee at their failure to understand what securing your services of course meant.

With hearty thanks,

Faithfully yours,

Theodore Roosevelt.

Mr. Augustus Saint-Gaudens,

Windsor, Vermont.[Hand-written postscript.]

I don’t want to slop over; but I feel just as if we had suddenly imported a little of Greece of the 5th or 4th centuries B.C. into America; and am very proud and very grateful that I personally happen to be the beneficiary.

I like the special bronze medal particularly.

In the meantime, as the result of the intimacy growing out of their cooperation in the matter of the inaugural medal, arose the scheme for the betterment of the coinage: the cent, which was later abandoned, the ten-dollar gold piece and the twenty-dollar gold piece, originated at the dinner mentioned at the outset of this article.

Considerable correspondence must have passed in short order between President and sculptor, but a letter written in 1905 by Mr. Roosevelt is the first in my possession dealing directly with the coinage. In view of the ultimate discussion raised by the desire for “high relief” and the objections made to it by the mint, it is interesting to see that the desire to depart from modern monetary requirements into more artistic fields was first shown by the President himself. The raising of the rim to permit the stacking of the coins, which he speaks of, was an obvious necessity, one always observed in the succeeding models, despite reports to the contrary. The President wrote:

The White House

WashingtonNov. 6, 1905.

My dear Saint-Gaudens:

How is that old gold coinage design getting along? I want to make a suggestion. It seems to me worth while to try for a really good coinage; though I suppose there will be a revolt about it! I was looking at some gold coins of Alexander the Great today, and I was struck by their high relief. Would it not be well to have our coins in high relief, and also to have the rims raised? The point of having the rims raised would be, of course, to protect the figure on the coin; and if we have the figures in high relief, like the figures on the old Greek coins, they will surely last longer. What do you think of this?

With warm regards.

Faithfully yours,

Theodore Roosevelt.

Mr. Augustus Saint-Gaudens,

Windsor, Vermont.

In Saint-Gaudens’s reply, which follows, he referred to the antagonistic attitude of the mint. The sculptor had already had one excessively disagreeable and stultifying encounter with that organization. It came about through his reluctantly accepting a commission to design the medal for the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1892. At that time he first created on the reverse of the medal a nude boy holding a shield. At once the forces for morality, for which our nation is famous, took the warpath. A second model was submitted, “draped.” This design was refused. Then Mr. Preston, at that time director of the mint, made a formal request for a third design. His letter stated that: “As soon as the reverse is received, preparation will be made to have it engraved immediately and to make a faithful representation of the same.”

Saint-Gaudens’s third design substituted an eagle for the boy; but scarcely had this reached the mint when it was again refused, with the announcement that a reverse, an invention from the hands of Mr. Charles E. Barber, the commercial medalist of the mint, had been combined with Saint-Gaudens’s obverse.

In the face of such an experience it is scant wonder that the sculptor dreaded further encounters. Unfortunately, his fears were fully justified. The mint’s jealousies of their old-time prerogatives proved so violent that the work failed to come through unscathed, despite the fact that the President accorded his support with all his joy of battle, as shown by his letters of January 6, 1906, May 26, 1906, and June 22, 1906.

By November 11, 1905, President and sculptor were fairly started on the task of producing the new coins. Here begins the correspondence covering their departure. Saint-Gaudens wrote the President:

Windsor, Vermont, Nov. 11, 1905.

Dear Mr. President:

You have hit the nail on the head with regard to the coinage. Of course the great coins (and you might almost say the only coins) are the Greek ones you speak of, just as the great medals are those of the fifteenth century by Pisanello and Sperandio. Nothing would please me more than to make the attempt in the direction of the heads of Alexander, but the authorities on modern monetary requirements would, I fear, “throw fits,” to speak emphatically, if the thing was done now. It would be great if it could be accomplished and I do not see what the objection would be if the edges were high enough to prevent rubbing. Perhaps an inquiry from you would not receive the antagonistic reply from those who have the say in such matters that would certainly be made to me.

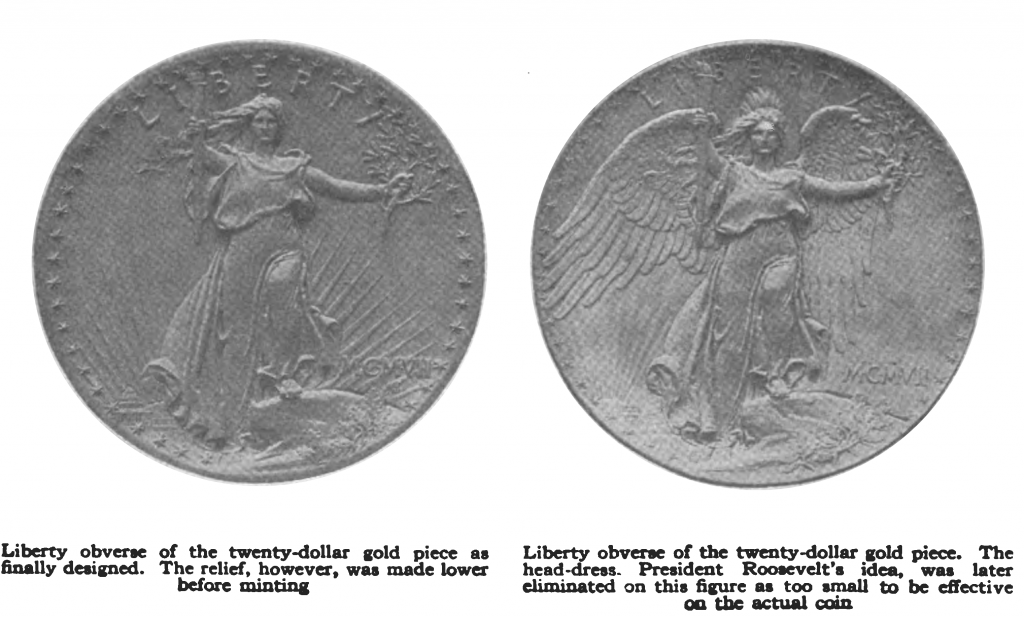

Up to the present I have done no work on the actual models for the coins, but have made sketches, and the matter is constantly in my mind. I have about determined on the composition of one side, which would contain an eagle very much like the one I placed on your medal with a modification that would be advantageous. On the other side I would place a (possibly winged) figure of liberty striding energetically forward as if on a mountain top holding aloft on one arm a shield bearing the Stars and Stripes with the words Liberty marked across the field, in the other hand, perhaps, a flaming torch. The drapery would be flowing in the breeze. My idea is to make it a living thing and typical of progress.

Tell me frankly what you think of this and what your ideas may be. I remember you spoke of the head of an Indian. Of course that is always a superb thing to do, but would it be a sufficiently clear emblem of Liberty as required by law?

I send you an old book on coins which I am certain you will find of interest while waiting for a copy that I have ordered from Europe.

Faithfully yours,

August Saint-Gaudens.

To which the President replied:

The White House

WashingtonNov. 14, 1905.

My dear Mr. Saint-Gaudens:

I have your letter of the 11th instant and return herewith the book on coins, which I think you should have until you get the other one. I have summoned all the mint people, and I am going to see if I cannot persuade them that coins of the Grecian type but with the raised rim will meet the commercial needs of the day. Of course I want to avoid too heavy an outbreak of the mercantile classes, because after all it is they who do use the gold. If we can have an eagle like that on the Inauguration Medal, only raised, I should feel that we would be awfully fortunate. Don’t you think that we might accomplish something by raising the figures more than at present but not as much as in the Greek coins? Probably the Greek coins would be so thick that modern banking houses, where they have to pile up gold, would simply be unable to do so. How would it do to have a design struck off in a tentative fashion—that is, to have a model made? I think your Liberty idea is all right. Is it possible to make a Liberty with that Indian feather head-dress? Would people refuse to regard it as a Liberty? The figure of Liberty as you suggest would be beautiful. If we get down to bed-rock facts would the feather head-dress be any more out of keeping with the rest of Liberty than the canonical Phrygian cap which never is worn and never has been worn by any free people in the world?

Faithfully yours,

Theodore Roosevelt.

Mr. Augustus Saint-Gaudens,

Windsor, Vermont.

Saint-Gaudens answered this letter as follows:

Windsor, Vermont, Nov. 22, 1905.

Dear Mr. President:

Thank you for your letter of the 14th and the return of the book on coins.

I can perfectly well use the Indian head-dress on the figure of Liberty. It should be very handsome. I have been at work for the last two days on the coins and feel quite enthusiastic about it.

I enclose a copy of a letter to Secretary Shaw which explains itself. If you are of my opinion and will help, I shall be greatly obliged.

Faithfully yours,

August Saint-Gaudens.

[Hand-written postscript.]

I think something between the high relief of the Greek coins and the extreme low relief of the modern work is possible, and as you suggest, I will make a model with that in view.

This is Saint-Gaudens’s letter to Secretary Shaw:

Windsor, Vermont, Nov. 22, 1905.

Hon. L. M. Shaw,

Secretary of the Treasury,

Washington, D. C.Dear Sir:

I am now engaged on the models for the coinage. The law calls for, viz., “On one side there shall be an impression emblematic of liberty, with an inscription of the word ‘liberty’ and the year of the coinage.” It occurs to me that the addition on this side of the coins of the word “Justice” (or “Law,” preferably the former) would add force as well as elevation to the meaning of the composition. At one time the words “In God we trust” were placed on the coins. I am not aware that there was authorization for that, but I may be mistaken.

Will you kindly inform me whether what I suggest is possible.

Yours very truly,

August Saint-Gaudens.

The President agreed with the sculptor, writing:

The White House

WashingtonNov. 24, 1905.

My dear Mr. Saint-Gaudens:

This is first class. I have no doubt we can get permission to put on the word “Justice,” and I firmly believe that you can evolve something that will not only be beautiful from the artistic standpoint, but that, between the very high relief of the Greek and the very low relief of the modern coins, will be adapted both to the mechanical necessities of our mint production and the needs of modern commerce, and yet will be worthy of a civilized people—which is not true of our present coins.

Faithfully yours,

Theodore Roosevelt.

Mr. Augustus Saint-Gaudens,

Windsor, Vermont.

This problem of the inscriptions proved a difficult one. Be it remembered that in the sculptor’s letter to the President regarding the inaugural medal he wrote, “The simplicity of inscription greatly aids the dignity of the arrangement.”

Such judgment was sound, and happily accomplished in the matter of this inaugural medal; but when it came to the coin, the sculptor found himself trammeled by antecedent and traditional elements and legal requirements, such as, the date on each coin, the word “Liberty,” the phrase “E Pluribus Unum,” the legend “In God we trust,” thirteen stars for the original States of the Union, forty-six stars for the States then in the Union, “United States of America,” and the denomination of the coin.

The suggestion of the word “Justice” was given up. In the case of the twenty-dollar gold piece the thirteen stars and the “E Pluribus Unum,” and in the case of the ten-dollar gold piece the forty-six stars, were placed upon the previously milled edges of the coin. The “In God we trust” was discarded as an inartistic intrusion not required by law. The President gave his sanction to placing the date of the coinage in Roman instead of Arabic figures. The word “Liberty,” the denomination of the coin, and the “United States of America” alone remained to be dealt with. The situation seemed clarified.

Unfortunately, however, the removal of the “In God we trust” drew down the lightning of public disapproval. The burden of the complaint was that the dropping of the legend was irreligious, although in this connection it was amusing to discover that Salmon P. Chase, who was Lincoln’s secretary of the treasury, sustained quite as stern a censure for placing these words upon the coins as was aroused by their removal. The President, with his usual delight in a fight, took the onus of this charge upon himself and stood the tempest remarkably well; but at a later date, the sculptor being dead, and Mr. Roosevelt no longer in a position to prevent it, the authorities in the mint reverted to their own sweet way, with the result that “In God we trust” and the Arabic numerals reappeared on the Saint-Gaudens’s coins, to the increased impairment of whatever of worth in the original design had been allowed to remain.

This is anticipating, however. To return to the present difficulties of Mr. Roosevelt and Saint-Gaudens, the next letter from the President shows how fully he shared the artist’s ideas regarding the atmosphere of the mint. The Shaw mentioned was L. M. Shaw, secretary of the treasury.

The White House

WashingtonJan. 6, 1906.

My dear Saint-Gaudens:

I have seen Shaw about that coinage and told him that it was my pet baby. We will try it anyway, so you go ahead. Shaw was really very nice about it. Of course he thinks I am a mere crack-brained lunatic on the subject, but he said with great kindness that there was always a certain number of gold coins that had to be stored up in vaults, and that there was no earthly objection to having those coins as artistic as the Greeks could desire. (I am paraphrasing his words, of course.) I think it will seriously increase the mortality among the employees of the mint at seeing such a desecration, but they will perish in a good cause!

Always yours,

Theodore Roosevelt.

Mr. Augustus Saint-Gaudens,

Windsor, Vermont.

The President’s philosophic attitude on any incidental mortality among the persons at the mint gave joy to the sculptor, who, no doubt, might well feel that he “owed them one.” So Saint-Gaudens’s next letter contains a forgivable chortle at the prospect of casualties among them, mixed, nevertheless, with a tincture of skepticism about the complete character of the destruction.

Windsor, Vermont, Jan. 9, 1906.

Dear Mr. President:

Your letter of January 6th is at hand. All right, I shall proceed on the lines we have agreed on. The models are both well in hand, but I assure you I feel mighty cheeky so to speak, in attempting to line up with the Greek things. Well! Whatever I produce cannot be worse than the inanities now displayed on our coins and we will at least have made an attempt in the right direction, and serve the country by increasing the mortality at the mint. There is one gentleman there, however, who, when he sees what is coming, may have “the nervous prostitution” as termed by a native here, but killed, no. He has been in that institution since the foundation of the government and will be found standing in its ruins.

Yours faithfully,

August Saint-Gaudens.

Some of the hurdles set up by the folk at the mint having been taken by artist and President, work progressed on the coins, and correspondence lapsed until late in May. On the twenty-sixth of that month Mr. Roosevelt wrote Saint-Gaudens, indicating that the President, still keen on the subject, had striven to ease the way of the sculptor in another direction. The President’s letters to Saint-Gaudens and to Secretary Shaw follow:

The White House

WashingtonMay 26, 1906.

My dear Mr. Saint-Gaudens:

I enclose a copy of a letter I have just sent to Secretary Shaw. I am delighted that you are getting along so well with the coin. It is one of the things in which I have taken the most genuine interest. I am so pleased that it is nearly concluded.

Sincerely yours,

Theodore Roosevelt.

Mr. Augustus Saint-Gaudens,

Windsor, Vt.[Hand-written postscript]

Use Latin or Arabic numerals as you think best, and could you show me the design when you get it ready.

This is the inclosure to Secretary Shaw:

The White House

WashingtonMay 26, 1906.

My dear Mr. Secretary:

Referring to the Saint-Gaudens’ correspondence there does not seem to be any reason for not putting the date on the coin in numerals. Those numerals are Latin and our figures are Arabic. If Mr. Saint-Gaudens is clear that the effect would be better if numerals should be used, I should give him his head about it. In such a case a “V” would have to be used and not a “U,” because of the simple reason that it would actually be a “V” and not a “U” that he was trying to put on. “V” means five; “U” is not a numeral at all.

I suppose you have sent Mr. Saint-Gaudens the permission to make a plaster cast of the present twenty-dollar gold piece.

Sincerely yours,

Theodore Roosevelt.

Hon. L. M. Shaw,

Secretary of the Treasury.

Saint-Gaudens could believe that the President might have his way with a mere secretary of the treasury, but he was not sure that even so redoubtable a President as Mr. Roosevelt could demolish the culture of the mint personnel. The next letter shows that the sculptor was fully alive to the herculean character of any triumphs over them.

Windsor, Vermont, May 29, 1906.

Dear Mr. President:

I have your letter of May 26th enclosing a copy of your letter to Secretary Shaw of the same date.

The reverse is done. But before showing it to you I wish you had the reductions made at the different reliefs. They will take some time. The obverse I am hard at work on. Its completion will not be delayed long and your “pet crime” as you call it will be perpetrated as far as I am concerned.

I have sent a practical man to Philadelphia to obtain all the details necessary for the carrying out of our scheme, but if you succeed in getting the best of the polite Mr. Barber down there, or the others in charge, you will have done a greater work than putting through the Panama Canal. Nevertheless, I shall stick at it, even unto death.

Faithfully yours,

Augustus Saint-Gaudens.

The lapse of time between the last letter of Saint-Gaudens and the next from the President might have indicated that Mr. Roosevelt hesitated about the combat. But, quite to the contrary, the fact that he was still game obviously follows from its context:

The White House

WashingtonJune 22, 1906.

My dear Mr. Saint-Gaudens:

Don’t forget to tell me when you want me to take up our brethren of the mint and grapple with them on the subject of the coins.

Faithfully yours,

Theodore Roosevelt.

Mr. Augustus Saint-Gaudens,

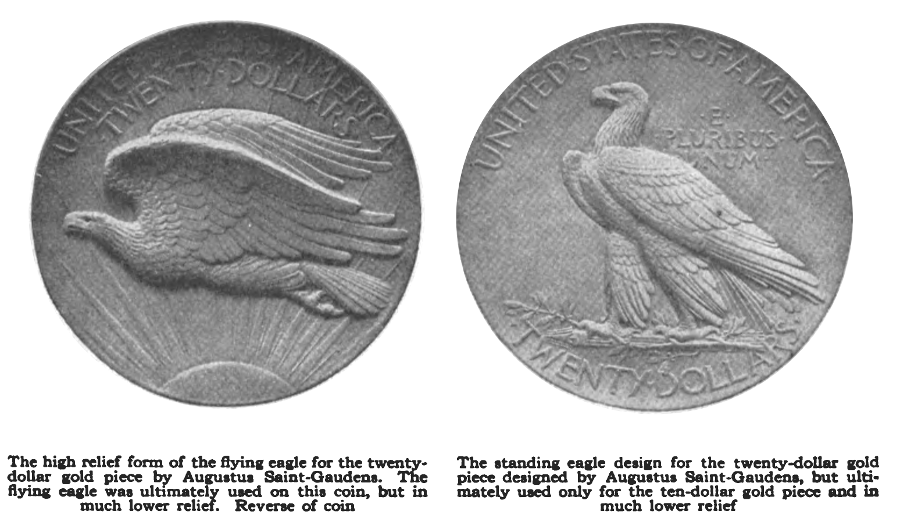

Windsor, Vermont.The problem of the eagle, which is mentioned in the ensuing letter, proved much more serious than Saint-Gaudens anticipated. The flying eagle, inspired by the design on the 1857 white cent, he ultimately abandoned in favor of a standing eagle. This latter conception he drew from designs he had used on such work as the Shaw Memorial in Boston, the medal struck to commemorate the inauguration of President Roosevelt, and the shield of the monument to President Garfield in Fairmount Park, Philadelphia. In all, for the coins, he created seventy models of this bird, and often stood twenty-five of them in a row in his studio at Cornish for visitors to number according to preference. He writes on the subject:

New York, June 28, 1906.

Dear Mr. President:

I thank you for your letter of June 22d. I will certainly inform you when your help will be needed with our friends in Philadelphia.

I am here on the sick list, where I have to remain in the hands of the doctors until the first of August, but my mind is on the coins, which are in good hands at Windsor.

The making of these designs is a great pleasure, but the job is even more serious than I anticipated. You may not recall that I told you I was “scared blue” at the thought of doing them; now that I have the opportunity, the responsibility looms up like a spectre.

The eagle side of the gold piece is finished, and is undergoing the interminable experiments with reductions before I send it to you. The other side is well advanced.

Now I am attacking the cent. It may interest you to know that on the “Liberty” side of the cent I am using a flying eagle, a modification of the device which was used on the cent of 1857. I had not seen that coin for many years, and was so impressed by it, that I thought if carried out with some modifications, nothing better could be done. It is by all odds the best design on any American coin.

Yours sincerely,

August Saint-Gaudens.

The President,

White House,

Washington, D. C.Saint-Gaudens was a very sick man during the whole of the period of the development of the coin designs. Hence his work did not progress with the customary energy, and hence the ensuing letters from the President. The “co-ordinate branch” referred to was, of course, Congress. Mr. Roosevelt mentions this body even more whimsically in his letters of October 1, 1906, and December 20, 1906, and in his autobiography, when he speaks of issuing the coins “before Congress assembled or could intervene.”

The White House

WashingtonOyster Bay, N.Y.

July 30, 1906.Personal

My dear Mr. Saint-Gaudens:

I do not want to bother you, but how is that coinage business getting on? This summer is the best time to settle it, because I would like to do it free from all supervision by the co-ordinate branch!

Faithfully yours,

Theodore Roosevelt.

Mr. Augustus Saint-Gaudens,

Windsor, Vermont.As the sculptor was too ill to reply, I wrote for him to the President, explaining the cause of the delay. This letter Mr. Roosevelt answered with his customary generosity, despite the fact that this situation was obviously putting him to inconvenience. He wrote:

The White House

WashingtonOyster Bay, N. Y.

August 6, 1906.My dear Mr. Saint-Gaudens:

I have your letter of the 2d instant. That is all right. What I shall probably do is to defer action until after the 4th of March next.

Give my warm regards to your father and say I hope he will soon be entirely well.

Sincerely yours,

Theodore Roosevelt.

Mr. Homer Saint-Gaudens,

Windsor, Vermont.The cause of most of the delay, however, was not due to the condition of the sculptor’s health, but to the impossibility of reaching a satisfactory understanding with the mint authorities. First, the Philadelphia officials, as might have been expected, complained that they found the relief too high, and that the sculptor must lower it and sharpen the details. Knowing that such modification must surely hurt the merit of the result, the sculptor agreed, only to meet with three more successive complaints of the same nature. On the third occasion he bought the two French coins I have mentioned—the gold twenty-five [twenty?] franc piece with the head by Chapl[a]in, and the silver two-franc piece, with the figure of “The Sower” [La Semeuse] by Roty. Next he asked the mint if they could strike what was struck abroad. Upon the mint’s replying, “Yes,” he ascertained the depth of relief of the French coins, and brought his new models to a shade under that. But again the mint proved recalcitrant; so the sculptor once more took his trouble to the President, who, as will be seen in the following letter, again gleefully went to the mat with the old enemy.

It is worth while noticing also in what ensues that it was now October 1, with Congress due to meet in a couple of months; hence the request in the last sentence of the first paragraph.

The White House

WashingtonOctober 1, 1906.

Personal

My dear Mr. Saint-Gaudens:

The mint people have come down, as you can see from the enclosed letter which is in answer to a rather dictatorial one I sent to the Secretary of the Treasury. When can we get that design for the twenty-dollar gold piece? I hate to have to put on the lettering, but under the law I have no alternative; yet in spite of the lettering I think, my dear sir, that you have given us a coin as wonderful as any of the old Greek coins. I do not want to bother you, but do let me have it as quickly as possible. I would like to have the coin well on the way to completion by the time Congress meets.

It was such a pleasure seeing your son the other day.

Please return Director Roberts’ letter to me when you have noted it.

Sincerely yours,

Theodore Roosevelt.

Mr. Augustus Saint-Gaudens,

Windsor, Vermont.The next letter from the President was even more urgent, probably because he still feared the “co-ordinate branch.”

The White House

WashingtonDecember 11, 1906.

My dear Mr. Saint-Gaudens:

I hate to trouble you, but it is very important that I should have the models for those coins at once. How soon may I have them?

With all good wishes, believe me,

Sincerely yours,

Theodore Roosevelt.

Mr. Augustus Saint-Gaudens,

Windsor, Vermont.Here some correspondence is missing, but as the following letter from Saint-Gaudens was sent only eight days after the one just given from the President, the action of the sculptor must have been speedy.

Windsor, Vermont, December 19, 1906.

Dear Mr. President:

I am afraid from the letter sent you on the fourteenth with the models for the Twenty-Dollar Gold piece that you will think the coin I sent you was unfinished. This is not the case. It is the final and completed model, but I hold myself in readiness to make any such modifications as may be required in the reproduction of the coin.

This will explain the words, “test model” on the back of each model.

Faithfully yours,

Augustus Saint-Gaudens.

The President’s enthusiasm on receiving the models was expressed with whole-hearted vigor. He replied:

The White House

WashingtonDecember 20, 1906.

My dear Saint-Gaudens:

Those models are simply immense—if such a slang way of talking is permissible in reference to giving a modern nation one coinage at least which shall be as good as that of the ancient Greeks. I have instructed the Director of the Mint that these dies are to be reproduced just as quickly as possible and just as they are. It is simply splendid. I suppose I shall be impeached for it in Congress; but I shall regard that as a very cheap payment!

With heartiest regards,

Faithfully yours,

Theodore Roosevelt.

Mr. Augustus Saint-Gaudens;

Windsor, Vermont.Throughout a greater part of these preparations Saint-Gaudens planned to complete the cent with the flying eagle, with the formal lettering treated in a new fashion, and to execute for the gold coins a full-length figure of Liberty mounting a rock, with a shield in her left hand and a lighted torch in her right, backed by a semi-conventional eagle with wings half closed. Eventually, however, the scheme proved impracticable.

The profile head Saint-Gaudens modeled in relief from a bust originally intended for the Sherman Victory, adding the feathers upon the President’s suggestion. Many persons knew it as the “Mary Cunningham” design, because posed for by an Irish maid, when only a “pure American” should have served for a model for our national coin. As a matter of fact, the so-called features of the Irish girl appear scarcely the size of a pinhead upon the full-length Liberty, the body of which was posed for by a Swede. Also, the modern American blue blood may delight in the discovery that the profile head was modeled from a woman supposed to have negro blood in her veins. Who other than an Indian may be a “pure American” is undetermined.

In reality, as in all examples of Saint-Gaudens’s ideal sculpture, little or no resemblance can be traced to any model, since the least taint of what he called “personality” in such instances caused him wholly to discard the subject.

Here is the sculptor’s first letter expressing his desire to comply with the President’s wish that the Indian head-dress be placed on the Liberty profile. Originally, of course, it had been proposed for the head of the figure of Liberty on the twenty-dollar gold piece. But when it had proved ineffective on so small a scale, the President had suggested the change. At first the sculptor made the addition against his better judgment; later, as will be seen, he came to the President’s way of thinking.

Windsor, Vermont, February 11, 1907.

Dear Mr. President:

I have received your letter of February the eighth regarding the Indian feather head-dress in its application to the one-cent piece.

I have already begun the trial in the way you suggest, so it should not be long before I will be able to tell you of the result. I shall endeavor to let you know with the utmost possible dispatch.

Faithfully yours,

Augustus Saint-Gaudens.

On the receipt of the new design the President answered:

White House

WashingtonFebruary 18, 1907.

My dear Mr. Saint-Gaudens:

I wonder if I am one of those people of low appreciation of artistic things, against whom I have been inveighing! I like that feather head-dress so much that I have accepted that design of yours. Of course all the designs are conventional, as far as head-dresses go, because Liberty herself is conventional when embodied in a woman’s head; and I don’t see why we should not have a conventional head-dress of purely American type for the Liberty figure.

I am returning to you today the model of the Liberty head.

With hearty thanks,

Faithfully yours,

Theodore Roosevelt.

Mr. Augustus Saint-Gaudens,

Windsor, Vermont.Evidently Saint-Gaudens did not think Mr. Roosevelt “one of those people of low appreciation of artistic things,” for the sculptor soon wrote:

Windsor, Vermont, March 12, 1907.

Dear Mr. President:

I send today to the mint the models of the twenty Dollar gold piece with the alterations that were indispensable if the coin was to be struck with one blow. There has been no change whatever in the design. It was simply a question of the thickness of the gold in certain places, and the weight of the pressure when the blow was struck.

I like so much the head with the head-dress (and by the way, I am very glad you suggested doing the head in that manner) that I should like very much to see it tried not only on the one-cent piece but also on the twenty-dollar gold piece, instead of the figure of Liberty. I am probably apprehensive and have lost sight of whatever are the merits or the demerits of the Liberty side of the coin as it is now. My fear is that it does not “tell’’ enough, in contrast with the eagle on the other side. There will be no difficulty of that kind with the head alone, of its effectiveness I am certain.

Of course there is complete justification for the small figure with the large object on the other side in a great number of the Greek coins, and it is with that authority that I have proceeded.

This all means that I would like to have the mint make a die of the head for the gold coin also, and then a choice can be made between the two when completed. If this meets with your approval, may I ask you to say so to Mr. Roberts, of the Mint? I have enclosed a copy of this letter to him. The only change necessary in the event of this being carried out will be the changing of the date from the Liberty side to the Eagle side of the coin. This is a small matter.

I enclose a copy of a letter I am sending today to Mr. Roberts.

Yours faithfully,

Augustus Saint-Gaudens.

It is good to know that your boy is getting well.

At last the President had won his point regarding the Indian head-dress. The following letter voices his pleasure over its success, and gives reasons as to why it should be there, very typical of his American outlook.

White House

WashingtonMarch 14, 1907.

My dear Saint-Gaudens:

Many thanks for your letter of the 12th instant. Good! I have directed that be done at once. I am so glad you like the head of Liberty with the feather head-dress. Really, the feather head-dress can be treated as being the conventional cap of Liberty quite as much as if it was the Phrygian cap; and, after all, it is our Liberty —not what the ancient Greeks and Romans miscalled by that title—and we are entitled to a typically American head-dress for the lady.

Faithfully yours,

Theodore Roosevelt.

Mr. Augustus Saint-Gaudens,

Windsor, Vermont.By this time the President and sculptor had cooperated for a year and a half. The sculptor had approached a definite result. The President had avoided congressional difficulties. He had persuaded Secretary Shaw to his way of thinking. Now Mr. Roosevelt and Saint-Gaudens were met with a fresh difficulty, which the President voices in the following letter:

The White House

WashingtonMay 8, 1907.

Personal

My dear Mr. Saint-Gaudens:

I am sorry to say I am having some real difficulties in connection with the striking of those gold coins. It has proved hitherto impossible to strike them by one blow, which is necessary under the conditions of making coins at the present day. I send you a copy of letters from the head of the Department of Coins and Medals of the British Museum, and from Comparetti. I am afraid it is not practicable to have coins made if they are struck with more than one blow. Of course I can have a few hundreds of these beautiful coins made, but they will be merely souvenirs and medals, and not part of the true coinage of the country. Would it be possible for you to come on to the mint? I am sure that the mint authorities now really desire to do whatever they can, and if it would be possible for you to go there I could arrange to have some of the Tiffany people there at the same time to see if there was anything practicable to be done.

With regard, believe me

Sincerely yours,

Theodore Roosevelt.

[Hand-written postscript]

You notice what Comparetti says about our country leading the way. I know our people now earnestly desire to do all they can; and I believe that with a slightly altered and lowered relief (and possibly a profile figure of Liberty) we can yet do the trick.

That the sculptor was only too anxious to experiment until satisfied with the result is shown by the work of his lifetime. But he had little strength left, and justly felt that it was not fair to his other commissions to devote to this one a larger share of his store of energy. Accordingly he wrote:

Windsor, Vermont, May 11, 1907.

Dear Mr. President:

I am extremely sorry that it will be wholly impossible for me to leave Windsor at present, but I am sending to Mr. Roberts, and if you so desire, to you, my assistant, Mr. Hering, who understands the mechanical requirements of the coin far better than I.

After all the question is fairly simple, and I have not the slightest doubt that making the coins in low relief will settle the matter satisfactorily. Greatly as I should like to please you, I feel that I cannot now model another design in profile for the Twenty Dollar gold piece. Indeed, as far as I am concerned, I should prefer seeing the head of Liberty in place of any figure of Liberty on the Twenty Dollar coin as well as on the One Cent. If the idea appeals to you, I would refine the modelling of the head now that I have seen it struck in the small, so as to bring it in scale with the eagle. I am grieved that the striking of the die did not bring better results. Evidently it is no trifling matter to make Greek art conform with modern numismatics.

Faithfully yours,

Augustus Saint-Gaudens.

Saint-Gaudens’s suggestion for the entire substitution of the profile for the Liberty figure was not accepted. The figure of Liberty remained beyond “one small issue of the coins,” as the President suggested in the next letter. It was used on the twenty-dollar gold piece for as long as the Saint-Gaudens’s design continued to be struck.

The White House

WashingtonMay 12, 1907.

Dear Mr. Saint-Gaudens:

All right. Your letter really makes me feel quite cheerful. I should be glad, if it is possible for you to do so if you would “refine” the head of Liberty; but I want to keep the figure of Liberty for at least one small issue of the coins. I look forward to seeing Mr. Hering.

With hearty thanks, believe me

Sincerely yours,

Theodore Roosevelt.

Mr. Augustus Saint-Gaudens,

Windsor, Vermont.In this final letter written by the sculptor to the President the ultimate design for the eagle was suggested and accepted:

Windsor, Vermont, May 23, 1907.

Dear Mr. President:

Now that this business of the coinage is coming to an end and we understand how much relief can be practically stamped, I have been looking over the other models that I have made and there is no question in my mind that the standing eagle is the best. You have seen only the large model, and probably on seeing it in the small will have a different impression. The artists all prefer it, as I do, to the flying eagle.

First, in that it is more on a scale with the figure of Liberty on the other side.

Second, it eliminates the sunburst which is on both sides of the coin as it will be if adopted as settled up to now.

Third, it is more dignified and less inclined toward the sensational.

Fourth, it will occupy no more time to use this model than it will to do the other work that will be necessary, and I think it is a little more favorable for stamping.

The majority of the people that I show the work to evidently prefer with you the figure of Liberty to the head of Liberty and that I shall not consider any further on the Twenty Dollar gold coin.

Faithfully yours,

Augustus Saint-Gaudens.

The sculptor died in August, 1907. Soon after the mint began to issue the coins with extremely poor results. Saint-Gaudens’s assistant, Mr. Henry Hering, who had personally carried on the alterations, asked why no heed had been paid to his request to see the die before the striking. The mint replied at random that it was forced, even in the present circumstances, again to reduce, on its own account, the proportional depths of the relief, and that in the process details were lost. Mr. Hering promptly exhibited three grades of relief reduced abroad to the same extent from the same original by the same machine that the mint employed. The details stood out quite as vividly in the low relief as in the high. Even this did not convince the mint, however, until at last Mr. Frank A. Leach, a new director of the mint, took a hand in the turmoil and brought the matter before the President for the last time, with the consequence that the mint accomplished the “impossible” and struck the coins.

In this fashion, therefore, the designs went forth, though, what with the lowered relief, most careless reproduction, and, soon after, additions of lettering and changing of Roman to Arabic numerals, the results appeared far from those Saint-Gaudens would have allowed had he been able to assert himself.

The President’s share in the new issue of coins, the thought, the patience, the unflagging enthusiasm, and the insistence that he brought to bear is a vivid example of his high regard for the need of artistic development in our national life.

Think of what problems the Chief Executive had on his mind during the years 1905, 1906, and 1907: the land frauds, the water-power question, the Indian Rights, civil service reform, antitrust legislation, Japanese immigration agitation in California, the Panama Canal, the Russian-Japanese peace treaty, and the voyage of the fleet around the world. Yet for all this the President could devote time and thought to questions of coin design, to battling with the bureaucracy of the mint, to foiling the unbaked opinions of Congress and, with the assistance of Saint-Gaudens, to setting before the public the results of a practical effort at refining American art. Nothing can show more conclusively how Roosevelt tasted all aspects of life and considered them as worthy of attention by those who sought, according to his own words, “the beauty of living and therefore the joy of life.”