Augustus Saint-Gaudens’ Eagles

Sculptor of over 200 works in marble and bronze, Augustus Saint-Gaudens had an international reputation and clientele for his portrait reliefs, decorative projects, and public monuments. His long career in New York, Paris, and Rome began as an apprentice to a cameo maker, and ended with a request from the president of the United States, Theodore Roosevelt, to design gold coins for the nation. In between these landmarks—humble and exalted—lay Saint-Gaudens’ life as a sculptor

In between these landmarks—humble and exalted—lay Saint-Gaudens’ life as a sculptor  of portraits, memorials, and architectural decorations. He was inspired by the golden age of Renaissance bronze statuary, committed to the overall relationships of architecture, design, and sculpture advocated by the Aesthetic Movement, and blessed by a personal genius for painstakingly researched yet astoundingly fluid imagery.

of portraits, memorials, and architectural decorations. He was inspired by the golden age of Renaissance bronze statuary, committed to the overall relationships of architecture, design, and sculpture advocated by the Aesthetic Movement, and blessed by a personal genius for painstakingly researched yet astoundingly fluid imagery.

The sculptor worked for almost two years between 1905 and 1907 on the design of the coins, each step of the way consulting with President Theodore Roosevelt. He died on August 3, 1907, before he was able to see the final coins struck by the U.S. Mint.

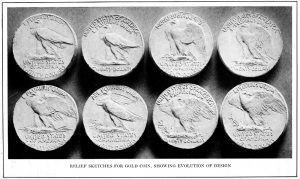

In 1920, the correspondence between the President and the sculptor regarding the coin design was made public by Saint-Gaudens son, Homer Saint-Gaudens. The letters, the sketches, plaster models, and pattern coins show how the design evolved over time.

Obverse of the $20 Double Eagle

Initially, the Liberty on the obverse was to have angel wings and was to hold a torch in the right hand and a shield in the left. Here is how the sculptor described his preliminary idea for the design: “I would place a (possibly winged) figure of liberty striding energetically forward as if on a mountain top holding aloft on one arm a shield bearing the Stars and Stripes with the words Liberty marked across the field, in the other hand, perhaps, a flaming torch. The drapery would be flowing in the breeze. My idea is to make it a living thing and typical of progress.“

At the suggestion of President Roosevelt, who thought that the traditional Phrygian cap of Liberty was not sufficiently symbolic of America, Saint-Gaudens added an Indian headdress. However, the headdress on the full-length Liberty was small and confusing. Therefore, it was discarded (but added to the Liberty head design that eventually ended up on the ten-dollar eagle coin). Also were discarded the shield and the wings. In addition, Saint-Gaudens experimented with the size of the Capitol building. Some of the ultra high relief pattern coins (and the 2009 ultra high relief double eagle coins from the U.S. Mint) had a small barely visible Capitol to the bottom left of the figure of Liberty. However, the final coins had a larger more distinct Capitol building. In some versions, the sun was rising on the left of Liberty from behind the Capitol. In all later and final versions, the sun rays shone from behind Liberty in the center.

In May 1907, Saint-Gaudens suddenly changed his mind about the design of the obverse, which was almost finished by that time, and wrote the President, “I should prefer seeing the head of Liberty in place of any figure of Liberty on the Twenty Dollar coin as well as on the One Cent.” A test pattern coin of this change was produced. However, the President responded, “I want to keep the figure of Liberty for at least one small issue of the coins.” The President’s word prevailed.

Reverse of the $20 Double Eagle

For most of the design process, the reverse of the twenty-dollar coin had a standing eagle with wings half closed similar to the one on the Roosevelt’s inaugural medal, which the sculptor produced in 1905. He believed the standing eagle design to be “the best” for the reverse of the coin (because it was of a similar scale to the figure of Liberty on the other side, it eliminated the sunburst from one of the sides of the coin, and it was in Saint-Gaudens’ view “more dignified and less inclined toward the sensational”).

Meanwhile, Saint-Gaudens separately worked on the design of a one-cent coin (which was not adopted). For the cent coin, the sculptor wanted to use a flying eagle, which was inspired by the design of the 1857 cent coin. Saint-Gaudens believed that particular eagle was “the best design on any American coin.” Apparently at President’s insistence, Saint-Gaudens’ design of the flying eagle for the one-cent piece was ultimately used on the twenty-dollar coin, while the standing eagle was later used for the ten-dollar coin.  The ten-dollar coin also inherited the obverse design of the one-cent coin (which was for a time considered for the twenty-dollar piece), the head of Liberty with an Indian headdress. So, although it may be a surprise to many, Saint-Gaudens did not specifically design the ten-dollar gold coin. The initial plan was to follow the practice of the U.S. Mint at the time and to scale down the design of the twenty-dollar coin for other coins so that all gold coins would be of a uniform design: a double eagle ($20), an eagle ($10), a half eagle ($5), and a quarter eagle ($2.5). However, President Roosevelt was reluctant to discard the versions of Saint-Gaudens’ designs that were not used on the twenty-dollar piece and decided to save them by placing them on the ten-dollar coin.

The ten-dollar coin also inherited the obverse design of the one-cent coin (which was for a time considered for the twenty-dollar piece), the head of Liberty with an Indian headdress. So, although it may be a surprise to many, Saint-Gaudens did not specifically design the ten-dollar gold coin. The initial plan was to follow the practice of the U.S. Mint at the time and to scale down the design of the twenty-dollar coin for other coins so that all gold coins would be of a uniform design: a double eagle ($20), an eagle ($10), a half eagle ($5), and a quarter eagle ($2.5). However, President Roosevelt was reluctant to discard the versions of Saint-Gaudens’ designs that were not used on the twenty-dollar piece and decided to save them by placing them on the ten-dollar coin.

On August 3, 1907, Saint-Gaudens succumbed to his prolonged fight with cancer, and did not survive to see the coins released later than year. His assistant Henry Herring used Saint-Gaudens’ variant designs for twenty-dollar and one-dollar pieces to finish the design of the ten-dollar coin. In 1908, the U.S. Mint planned to use the double eagle design on the half-eagle and quarter-eagle coins, but before the work was complete President Roosevelt’s friend suggested a new revolutionary design for those coins. However, that is a different story deserving a separate article.